Joining Rover in September 2023, my first impression on day one was, “Wow. They are really organized and thoughtful about planning and project management.” From detailed formal documentation provided by Product, UX Design, and Engineering to the processes before launching features, I was amazed.

One of Rover’s foundational technical principles is “build like your pet depends on it” – and that couldn’t be more true. Roverines prioritize quality, security, and stability, especially for the core product, because pets and their pet parents (myself included) rely on the software at all times.

Of course, it’s also important to build quickly and learn what works vs what doesn’t for our community. These two concepts, a focus on building quality and also building quickly, are huge themes in our approach to technical planning. We want to ensure a good balance – more on that later!

Joining a Working Group

Fast forward to spring 2025. I got the opportunity to join a working group on improving our technical planning process. At Rover, working groups are commonly used to address issues that span our technical teams. They are sponsored by an individual at director-level or above and are made up of individuals across multiple teams and departments at all different levels. This makes sure we have the right people for the discussion and leadership buy-in to tackle our goals. I love this aspect of Rover’s engineering culture – we all are empowered to contribute and make positive changes.

When asked to join, my first thought was, “This is so cool! I get to be a part of the organized, thoughtful approach to planning that struck me on day one.” It was also a great opportunity to bring some pain points my team has with technical planning and ways we’ve adapted the process to fit our needs. Plus, I was interested to hear from others – we have so many different types of projects at Rover!

Our working group was 15 people spanning various teams (from infrastructure to niche product engineers) and all levels from junior to staff engineer, manager, and director. Our day-to-day work is so different, but we are all affected by technical planning.

Rover’s Technical Planning Challenges

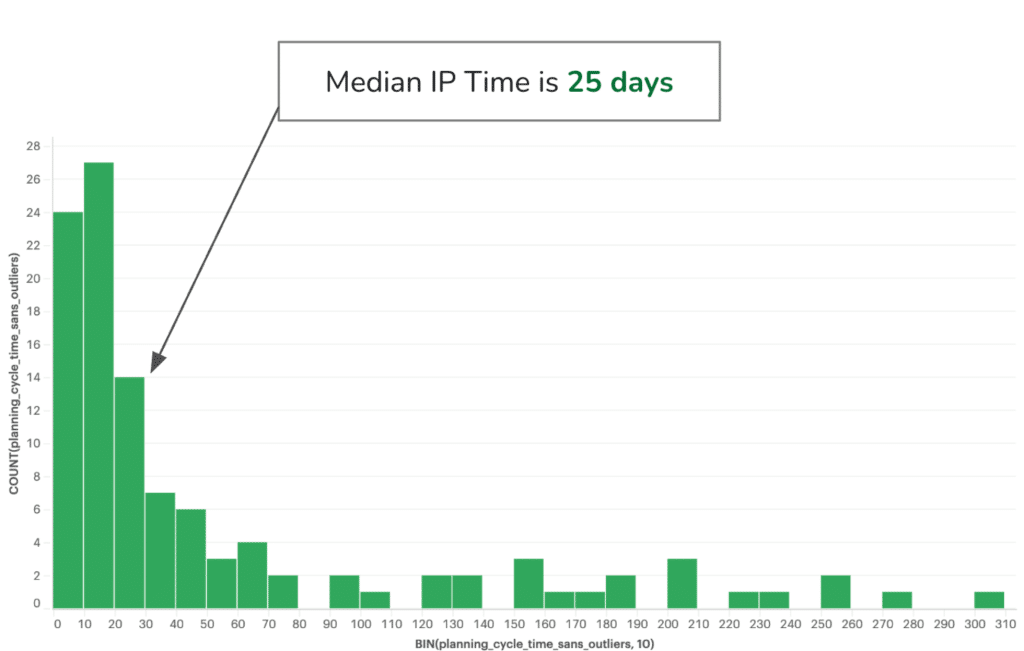

During our first meeting, we reviewed a chart with data on the time it takes engineers to write our “Implementation Plan” (IP) documentation, a core part of our existing planning process. This IP document has a set template with things like “Background”, “Risk Assessment”, “Implementation Details” spanning infrastructure plans to user accessibility, “Observability and Monitoring”, etc. It’s very lengthy and detailed.

The data showed our median time spent creating these documents was 25 days! (Woah!) But the distribution is spread – highly peaked on the shorter timescales, with a long tail extending to hundreds of days for really complex projects. This was astounding to all of us! It begged the question – are we putting too much detail in the IPs, venturing far into diminishing returns? Is it counterproductive? Maybe this one-size-fits-all IP strategy isn’t working for projects of different risk and complexity. How have our own engineering culture and processes influenced this behavior?

Making Improvements

Our working group’s goals became:

- Update the IP template and surrounding documentation.

- Define a technical project planning framework – a simple, adaptable guide for teams to classify projects and choose better project planning strategies. No more one-size-fits-all approach!

Off we went! Several meetings later, with small-group discussions, collaborative brainstorming, and various draft documents, we concluded to move from an IP to a Request for Comments (RFC) document. RFCs are used by many organizations (examples: 1, 2, 3, 4).

For our RFC documents, we want to focus on high-level planning, the big decisions like, “Should we use this technology or that?”, “How should we structure our data model?”, “Are there alternate approaches that could achieve the same goals?”.

We want to encourage discussion amongst engineers before we start writing individual tasks of work. Previously, IP documents could get into the weeds, scoping out individual tickets of work, before discussion. Now, we want to encourage more collaboration at early stages – opportunities to catch pitfalls, design streamlined solutions, and get the team informed and ready to build!

This decision actually ties to one of our other foundational technical principles: “innovate where it counts.” This means we prefer proven, industry-standard technologies and best practices so that we can build on that sturdy foundation and innovate on unique aspects of our business where appropriate.

We don’t need to reinvent the wheel for technical planning – many successful companies use an RFC. We want to learn from their templates and examples, then customize for our technical organization.

Different Elements of Technical Planning

There are so many different aspects of technical planning, though, it’s not just IPs or RFCs. Sometimes you might like to build a small proof of concept (POC) to test an idea, other times you need a short spike – an investigation to learn about a technology or reduce uncertainty or risk. There are even times you can jump to writing out tickets of work that communicate exactly what tasks need to be done – a form of planning that is essentially documentation without a big formal document.

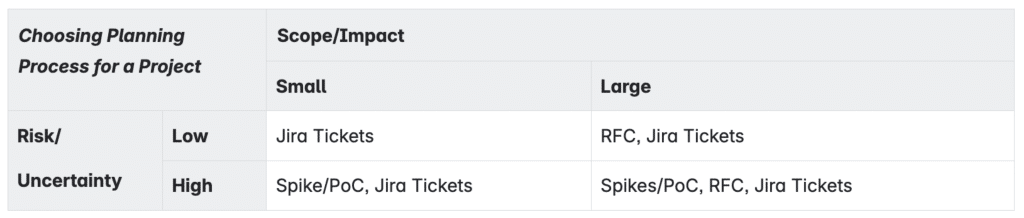

Our group created a framework for choosing planning processes that include one or a combination of these planning strategies.

Consider the risk/uncertainty – is it low or high? For example, consider, “Does the engineering team have a consensus about the approach after reading the (Product-provided) Functional Specification?” If the answer is yes, that seems to be low uncertainty. If the answer is no, it’s high uncertainty.

Another axis is scope/impact. For example, “Does this change impact multiple teams?” If the answer is just 1 team, your team, then it’s probably small scope. If the answer is several teams, that’s a large–scale project where you should probably have an RFC document to discuss the changes with those affected teams. The largest, highest–risk projects may need initial spikes or POCs to investigate initial details, then an RFC, and later writing tickets. These big projects should maybe be broken down into phases with documentation for each phase’s goals and deliverables. On the flip side, small projects may only need tickets – you know exactly what needs doing!

In general, we agreed that all projects benefit from organizing key details in a “Project Cover Sheet” that lives in the Epic for our tickets. It’s a central location and checklist to collate all project documentation – like the Functional Spec from Product, design documentation, test plan, any dashboards for monitoring, etc.

Results

Our working group came to these conclusions, wrote up our deliverables, and shared them with the wider technical organization. Now we are starting to adopt our new principles and I recently wrote my first RFC!

We’re going to see how the next few months go, gathering feedback and data along the way! It’s all so true to what I first observed at Rover – the thoughtfulness around planning and project management plus a spirit of innovation that drives continuous improvement. We all contribute to refining our processes. It’s such a great engineering culture to be a part of!

Speaking of which, if you’re interested in working with us at Rover (and want to take part in our technical planning process!), check out our Engineering Careers page at: https://www.rover.com/careers/engineering/